I recently wrote (Looking Back At a Rocky Little League Start) about my unplanned entry into Little League coaching when my son was seven years old. That had been coach-pitch ball, where everyone batted each inning, no matter how many outs were made, and no score was kept, except by the players of course.

The following spring we were excited by the prospect of real baseball in the Little League minors. One afternoon, my son, a friend of his, and I were at our neighborhood park engaging in a little preseason baseball practice. A Little League team, or as we later learned, two teams—minor and major league affiliates—were practicing on the diamond, while we were in deep right and center field. This is not a regulation park with Little League fences, so the field is regularly used for frisbee tossing, sunbathing, etc. when games are not being played.

My son and his friend caught the talent-scouting eye of one of the coaches on the diamond. The coach walked over to talk to us to see what was what. He asked the boys if they played Little League. The friend did, but was about to move out of town. All the interest was then focused on my son. The coach, whose name was Jon, invited him to join in the next team practice. Actually, since it was an unofficial practice, he called it a get-together or something like that.

I remembered a story I’d read in the local paper a few years before about a coach in our town being arrested at a ball field right in front of his team for conducting an early unauthorized Little League practice. The league president had called the cops on him supposedly for practicing on a city field before receiving permission from the city. I had thought it was crazy, and that the more practice kids got the better, but there’s no denying the early bird coach had probably been seeking an advantage. These coaches must have felt the heat was off as far as any consequences as extreme as arrest went. They probably would have said that everyone was doing it.

I guess my son and I were flattered by Jon’s desire to have my son practice with his team. Or, more likely, I was flattered, and my son was just happy for the chance to get started with real baseball. We came to the next unofficial practice of these Little League Red Sox. We were delighted to see that Wilson, one of our favorite kids on the “traveling team” from the previous year was there as well. Since his older brother was on the major league Red Sox, Wilson was guaranteed a spot on its minor league affiliate, which made it all the more attractive to us.

What a step up it was for my son to be practicing with experienced players under experienced coaches! Jon’s son was on the minor league team, and he seemed to be a very nice kid, which won Jon points with me as a potential coach for my son. I liked the way the coaches treated the kids and ran the practice, so both my son and I were quickly sold on the idea of being on the Red Sox. I planned to sign up to be eligible for coaching again in case my son’s team had need of coaching help. It felt like the Red Sox were our team already.

The player draft was conducted before one of the Little League meetings. Jon came from the draft to the meeting where I was waiting and told me there had been no problem; the Red Sox had landed my son. I glanced at the list of players in the draft Jon was holding and thought I saw next to my son’s name the notation “Will only play for Red Sox.” Since that went far beyond anything we would ever have said, stretching a strong preference into a requirement, I realized there had possibly been some chicanery involved in getting my son. Assuming I saw what I thought I saw, I still don’t know if the statement was actually used or just held in reserve in case someone tried to draft my son before the Red Sox could. I never said anything to Jon about it; and, since I didn’t, the only sure thing is that I let it go by without comment despite my suspicion.

It appeared that I was going to be Jon’s main assistant coach. I was looking forward to helping and learning from Jon and was glad not to have the responsibility for a team, which had been thrust upon me at the last minute a year before. There seemed a good possibility that I might inherit the managerial role the following year after Jon had moved up with his son to the majors. For now I was doing whatever Jon asked me to, whether putting balls on the tee for batting practice or hitting ground balls to players.

During a practice shortly before the season was to start Jon asked me, somewhat dubiously I thought, “Can you handle this team?” Thinking he needed to go to the bank before it closed or something and wanted me to run the practice for half an hour or so, I said I thought I could for a while. But no, he meant could I take over the managing job for the season! His son was being called up to the majors along with a couple of the other older players, and Jon was moving up with him to help coach at the next level. This meant I would be on my own and with a team depleted of some of its best players. It seemed to be my fate to have a team thrust on me each year. Despite my doubts, I said yes I would try, part of the reason being that I didn’t want to take a chance on whoever else might get the job at that point, as there were no other candidates on Jon’s coaching staff.

If I had been reluctant to take on the seven-year-old coach-pitch team the year before, I really felt in over my head now. This was real baseball, and I imagined it as being close to what my only experience with organized ball had been when I was a teenager. What about run-down pickle drills? What drills would I use at all beyond the most basic fielding and throwing to bases? Could I throw strikes in batting practice? My coach-pitch experience should help there. I would have to start learning the Little League rule book. I would at least be able to know for a fact that no rules were being evaded or stretched by our team. Teaching kids how to pitch? I’d never pitched. Time to order some videos and books! I did find some that were helpful, but time seemed so short.

The two best older players left on the team, Tim and Dennis, nine and ten years old, respectively, were unhappy because they hadn’t been called up to the majors along with the others they liked to consider their peers. There was some talk of their quitting, but fortunately they came to the first practice with me as the manager. Dennis’s mother even helped out by throwing some batting practice.

We had not a single experienced pitcher now, but had some kids that wanted to try. I had already identified Tim as the one kid with the arm, control, and confidence a pitcher needs, but he was untested. Beyond him I wasn’t sure who the best prospects were. I held a couple of tryouts using a pitching target I had just bought. It was a big tarp mounted on a frame about five feet high and three feet wide with a Little League size strike zone cut out in the middle and with net pockets to catch balls in the strike zone, including special small pockets for balls put on the corners of the strike zone. Most of my pitcher candidates had trouble hitting the target at all, I mean the whole tarp, never mind the strike zone. Dennis, the tall ten-year-old I’ve already mentioned, was promising I thought; but, upon further consideration, he was sure that he didn’t want to pitch. Too much pressure obviously. I put him at catcher, as I wanted a good player there. My son was someone to consider for the future. Mark, another ten-year-old was sure he wanted to try.

I had just bought. It was a big tarp mounted on a frame about five feet high and three feet wide with a Little League size strike zone cut out in the middle and with net pockets to catch balls in the strike zone, including special small pockets for balls put on the corners of the strike zone. Most of my pitcher candidates had trouble hitting the target at all, I mean the whole tarp, never mind the strike zone. Dennis, the tall ten-year-old I’ve already mentioned, was promising I thought; but, upon further consideration, he was sure that he didn’t want to pitch. Too much pressure obviously. I put him at catcher, as I wanted a good player there. My son was someone to consider for the future. Mark, another ten-year-old was sure he wanted to try.

A stressful non-baseball problem also arose before our first game. The team had gotten a late addition to its roster in the person of Don, a big ten-year-old with a strong arm, which made me think of him as another potential pitcher. A couple of days after Don showed up I got a call from the mother of Rob, a returning nine-year-old whom I was considering for second base. Rob’s mother was extremely upset that Don had been added to the team. A few years back in the early grades, Rob’s mother had gone high up the school hierarchy to ask for protection for Rob against Don, whom Rob was afraid of. After that, according to Rob’s mother, Don’s mother had accosted her in public and physically threatened her.

I have no way of knowing what the actual situation was between the boys, but I’m sure both mothers had been acting forcefully, in the way that came most naturally to them, in defense of their sons, as they saw it; Rob’s mother to protect her son from bullying (as she perceived it) and Don’s mother to protect her son from unfair accusations and classification (as she perceived it). Whatever had happened, and it had been a few years now, Rob’s mother had gotten a restraining order against Don’s mother back when the original incident took place and was still scared of her.

Much as I hated to be involved, all I could see to do was to call Don’s mother to arrange for him to go to a different team, as he was the newcomer with no ties. To my surprise, she was adamant that Don would not move, that she had no problem with the situation, so Rob’s mother should move her son if she had a problem. Furthermore, she would sue Little League if we “discriminated against” Don by attempting to move him. Obviously, I was stepping into a drama that had been going on for some time, so that what seemed a very reasonable request to me was being perceived as yet another unfair move against Don to be resisted by all available means.

I called Rob’s mother to bring her up to date and see how she felt. She had already talked to Rob about the possibility of his moving to another team; his team loyalty was stronger than whatever residual fear he had of Don, and he wouldn’t consider changing teams himself. That was heartening. This parental conflict was more than I had bargained for, but I couldn’t see anything to do but to go ahead with both boys on the team, keep an eye on things, and hope for the best since the initial conflict had been years in the past.

Don’s mother had showed up with him the first day, ready to become a coach for the team and fully assuming she would, as she had previously coached Don’s soccer team. I only had one assistant coach at the time, the mother of one of the eight-year-old rookies. She was good with the kids, but not very knowledgeable about baseball. She had signed on to coach with Jon mainly to help keep her son, who was a reluctant participant in Little League (only playing at her insistence, I gathered) and prone to bug watching during team practices, on task. So, I could have used the help. But given the situation, I told Don’s mother I was not going to have her as a coach. That evidently surprised her as much as her unwillingness to consider moving her son to another team had surprised me. She said “You’re bold,” I believe the adjective was, but, despite some talk about taking it to the league president, she accepted my decision, and later on in the season became pretty friendly.

I was probably more nervous than the kids about our first game. I didn’t know what to expect. I had barely had a chance to decide who would play where. Wilson and my son were rookies starting at third and short, respectively; Tim and Dennis were new to pitching and catching; and none of the other starting infielders had played their positions before.

The kids looked sharp and focused in their pre-game fielding practice. Tim started the game for us on the mound (figuratively speaking, since our league’s “mounds” were as flat as the rest of the infield, though there was a pitching rubber, which always had a hole in front of it). The Little League pitching rules then in effect (they have since moved to limits on actual pitches per game and week) placed limitations on the number of innings in which a player could pitch. My plan was to get three innings out of Tim and then bring in someone else, leaving Tim eligible to pitch again in our next game, which was only two days off. One pitch in the fourth inning would have made him ineligible for three days.

At the end of Tim’s three innings, I was proud of how the team had been playing and relieved at the way things were going. Tim had pitched well, and our team had a 4-3 lead. Win or lose, this was a respectable showing, and my fears of a fiasco seemed unfounded. Things went downhill fast after Mike was replaced at pitcher. Mark pitched the fourth inning and only got two outs, while giving up five runs. The rule in our minor league was that a team could only bat once through their order in an inning until the final inning. We batted ten or eleven in our league, as we played with four outfielders and had the option of an extra hitter. The fifth inning was worse, as Don failed to get anyone out before I switched to my last known available pitcher to finish it. That last pitcher happened to be the eight-year-old son of the manager, and I would have to stick with him, no matter what. He let in a couple more runs, but struck out the last batter of the inning for the only out we got. We failed to score in the bottom of the inning, and we were now down 15-4 through five.

The Indians’ manager came over to talk to me somewhat apologetically. He wanted me to know that he knew what it was like to be in my shoes, for the previous year his team had won only one game and that was by a forfeit (in other words, they had lost every game). He may have sensed we were on the brink of a similar season with a rookie manager and a depleted team with obvious pitching problems, or maybe he was just recalling similarly lopsided games. I appreciated his words. At the same time, I couldn’t help thinking: why not tell your players to swing the bat if the pitch is at all hittable? Under similar circumstances now, I would probably make that suggestion, but as a rookie manager I felt more inhibited I guess.

The point of the managerial conference was that, being down by more than ten runs after five full innings, under regular Little League rules our team would have had to concede the game, but our league allowed the manager to decide whether to continue or not. A factor to take into account was that teams would not be limited to one time through the batting order in the sixth inning, which is the last inning in Little League. I suppose the memory of our good start and that strikeout of their last hitter influenced my decision to gamble on getting them out fairly quickly, so that we could get one last at bat and hopefully score a few runs to end the game on a somewhat positive note. I probably didn’t really think through the worst case scenario thoroughly, focused as I was on the potentially upbeat ending.

I soon regretted my decision to continue playing. Though the sixth inning started off well enough, with two of the first three batters being retired, from then on the inning became a walkathon, as the batters all seemed to come up looking for a walk, which was indeed to be found. Those two early outs proved to be a curse, as they held out the hope that the next batter could always be the last. It wasn’t as though the opposing batters were all walking on four wild pitches; there were some excruciating walks on 3-2 counts. At this point an adult umpire would almost surely have called any pitch a kid could reach with a bat a strike, but the teenage umpire was sticking by the strike zone as he saw it without considering the score or the fact that the hitters weren’t swinging at anything. Not then, nor ever, did I complain about an umpire’s call, but I think it would have been a good idea to have suggested expanding the zone a little to him if I had thought of it before the inning had started. As the opposing team was not limited to one turn in the last inning, players were coming up for the second time in the inning, and walks continued to bring in runs. I felt bad for the rookie pitcher, needless to say. It was another of those infinite-loop nightmares.

With nine more runs already in, and the score standing at 24-4, there was no way to foresee when or if we’d ever get that final out. Better late than never, I asked for a timeout, walked out to the mound, and waved the team in for a conference. “What’s he doing now?” one of the opposing team parents asked disgustedly within my wife’s hearing. “OK, guys, we’re going to call it a day. Remember, it’s only one game.” “Finally!” said Tim. One of the fathers later told me that Tim’s post-game assessment had been “This team sucks!” What a coaching debut!

Despite the ignominious conclusion of our game, I could see reason for hope. We had had the lead after three innings. We had made plays! If you’re a beginning coach in your team’s first game, the sight of your infielders fielding ground balls and making good throws to first base, where the first baseman catches the ball for the putout—no matter how routine the play should be—is indescribably beautiful. All our trouble had come after I’d taken Tim out. Given that it was the team’s first game and none of the pitchers had ever thrown a pitch in a game, it probably wasn’t too surprising that most of them had trouble throwing strikes. The importance of pitching and experience was not a new discovery. With Tim pitching in our next game, we should have a fighting chance, depending on the quality of the opposition.

I guess it was the combination of the devastating score and the other manager’s reference to their winless season that nonetheless made thoughts of an 0-18 record for the year start to prey on me after only one game. Would I be hoping for a forfeit before the season was over, so I could at least match last-year’s Indians with that one “win?” Would the kids realize there were reasons for optimism, or would they be crushed beyond hope? Would kids start quitting the team? Would the parents start to mutter about my incompetence? What about my son? Had I shattered his confidence by leaving him out there to walk so many batters? All of my doubts about being ready for coaching were weighing on me.

We didn’t have long to wait for our next crack at a victory, as we only had one day off before taking on the Cardinals. Nonetheless it seemed like a long time to me, and it was long enough for us to hear one of my son’s friends say in a matter-of-fact, not a teasing, way that we must really be bad to have lost to the team he knew hadn’t won a single game the year before. I wasn’t pessimistic, just worried.

Contrary to my fears, the kids seemed to be fine. No one failed to come to the game, and they showed no signs of being disheartened. They were not sullen or mutinous. They were kids from eight to ten years old, eager, almost all of them, to play baseball, the greatest game ever invented. Tim was our starting pitcher again. I planned to use up his weekly allotment of six innings in this one game, so long as he seemed OK.

No matter how he may have felt about his team’s chances, Tim pitched even better in this game; and we were still making plays. Through four innings we had a slim 3-1 lead; and each team had recorded only one hit. Then in the fifth we started to hit; we scored three runs in both the fifth and sixth; and we took a 9-2 lead into the bottom of the sixth. In that last inning, with one run in, the Cardinals had runners on first and second with no outs. Then Tim struck out a hitter and got the following one out on a popup.

The next batter hit a ground ball to the third-baseman Mark, who fielded it cleanly and then looked up to see the large runner from second coming right at him. To my great relief, instead of throwing to first base, Mark did the right thing, tagging the runner out, though rather harder than necessary, as often happens in the Little League minors. It was one of the most memorable outs I’ve witnessed in my entire baseball-watching life. Thank you, Mark!

There were smiles all around on our side and great relief for at least one of us. The winless season was no longer a possibility! Tim had pitched a four-hitter with twelve strikeouts, the biggest strikeout coming in the fifth to end the inning with the bases loaded. Dennis was going to be strongly encouraged, maybe even pressured a little, to get over his reluctance to pitch.

Our team would go on to win its next nine games, with both Dennis and my son joining Tim in pitching the team to wins along the way, before losing by one run to the Cardinals in our third meeting with them. Suddenly we were among the elite teams in the city. But with that came the coach’s burden of higher expectations. There was really no escape from the pressure that year, but the second kind is better.

An important thing coaching has taught me is that kids naturally have the highly desirable combined ability to both treat their current activity or contest very seriously and to recover completely from what seems briefly to be a devastating setback or defeat. This was one of the things I had been hoping to instill in the kids on my team: try your best, but don’t dwell on losses. It turned out they didn’t really need to be taught that, if such a thing could be taught except by example anyway.

Being responsible for preparing the team to play its best—to win if possible—and imagining (rightly in some cases) that the other parents were just as anxious about their child’s and their child’s team’s game success as I was, was both a burden and a privilege. I’ve observed that parents seem more anxious about their children in sports when they are younger, I suppose because they seem more vulnerable; and, for some, because of the parents’ hope that they will see their child blossom into a star athlete.

Looking at pictures of that team, I am struck by how little they were. How could their winning or losing baseball games have taken on so much importance to me and to other parents? Part of it is the natural desire of the teacher to see his students perform well, whatever skill they are supposed to have mastered. Obviously, being the father of one of those little players who also took baseball seriously was the main reason, but I didn’t share many of his childish enthusiasms.

I think that points to the answer: baseball provided a bridge I could cross over to his world where play was extremely serious, yet fun, a bridge back to childhood itself. That feat is pretty much impossible for most of us through watching or joining in on other types of play—playing Star Wars, say, to take an example from my son’s childhood. I think the rules and the scoring of baseball are part of what makes the bridge work: the game is still fun and dramatic for grownups. And in organized baseball, the children are able to come partway across the bridge in the other direction toward the adult world. This ambiguous and unconscious mixing of worlds may be the reason that some parents behave so badly, so childishly, at their kids’ games. This would be an inherent danger.

I don’t fully know what to make of the sort of mania we can get into following our young children’s organized games, but I know my son and his friends have good memories of their early Little League days and so do their parents, so I guess no further analysis is needed in way of justification.

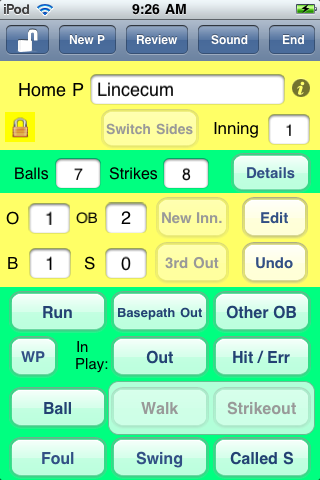

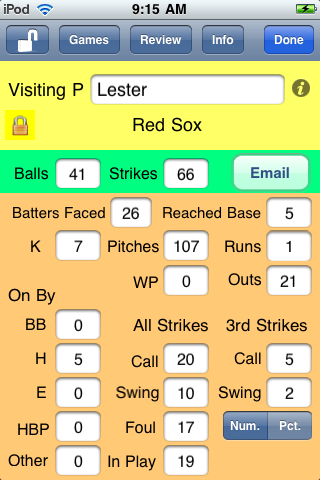

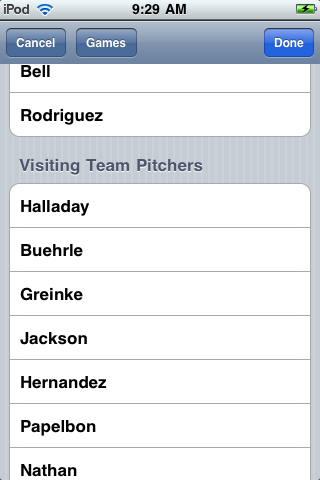

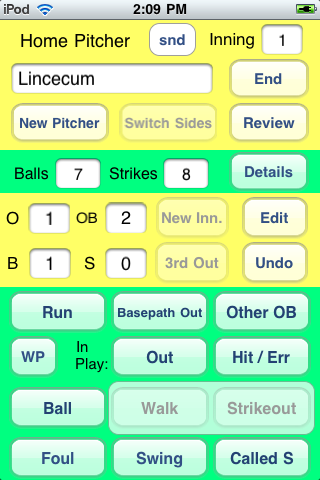

OnScreen

OnScreen

OnScreen

OnScreen OnScreen

OnScreen